Medtronic

2014

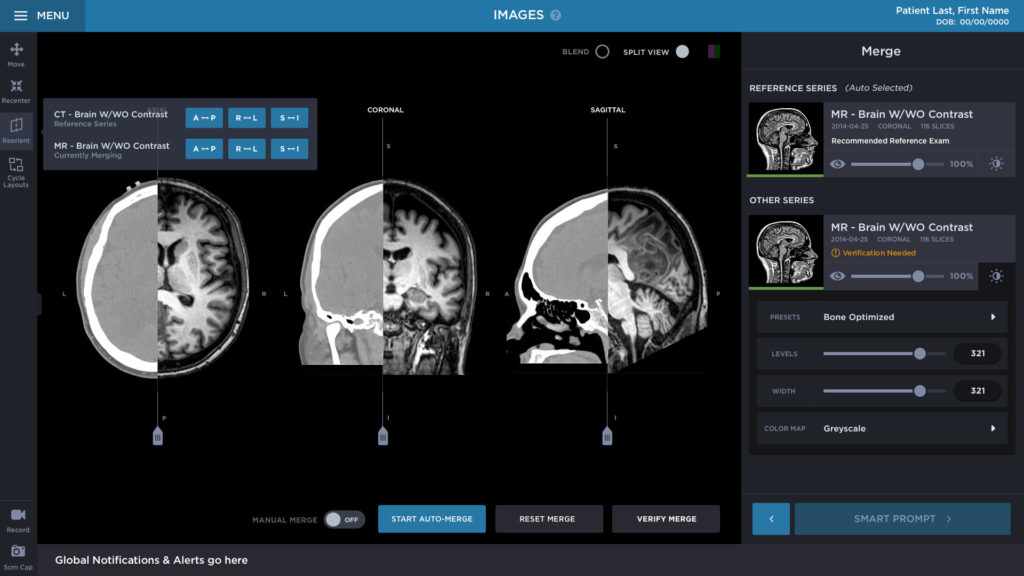

Medtronic is a global leader in surgical navigation. Their StealthStation, a hardware and software system that enables surgery on the brain, spine and other delicate areas of the body, was due for an update—the S8 system. They partnered with Slice of Lime to modernize the software and bring it to the forefront of the field. The project was complex and, given the nature of the product, important to get right.

Background

The project took significant amounts of the company's talent and time and contractually stipulated an unusual approach to fielding the team. Instead of people working as a single team, Medtronic asked for three teams to work in parallel, each team with slightly different parameters. All teams had to use a human centered approach, but one was limited to updating the current UI (the conservative track), one was given free range to consider anything technically possible and surgically sound (the blue sky team) and one had to base their work in collaboration with a third party designer who had already worked with Medtronic for months before we came on board (the Fletcher team—the name of the non-Slice of Lime designer). With these stipulations, work began.

Guide the Team

Teams began with a discovery phase to understand the basics of navigational surgery. This work could be shared amongst the three design teams before they'd split off to work within their individual parameters. But with seven designers (one of whom wasn't a Slice of Lime employee) and six clients (two per team), the project needed coordination to gain momentum.

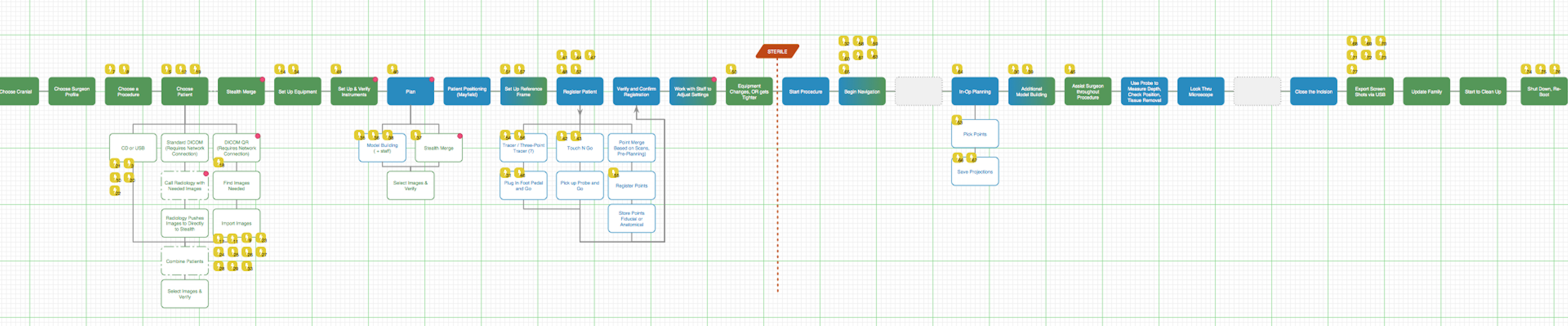

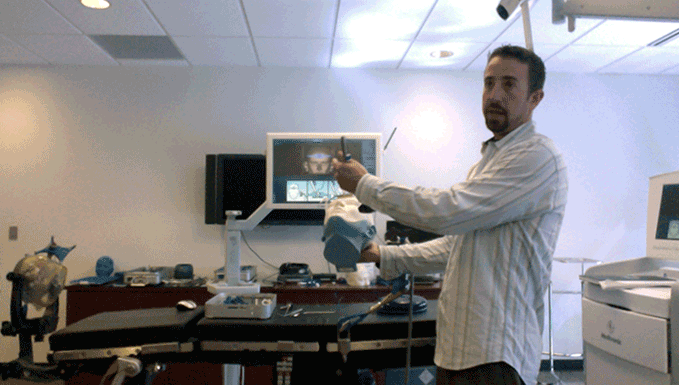

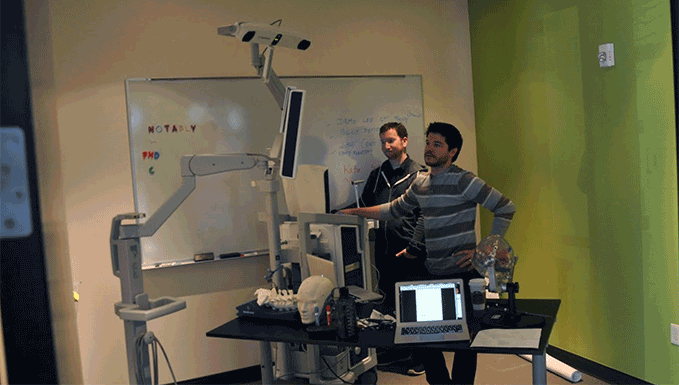

I directed all teams to start by building a universal customer journey as a common framework. I'm a proponent of journey maps as they outline all the steps necessary in a process and allow many types of information to be plotted onto them like the people involved, issues in the current process, alternate paths, etc. Based on this starting point, our full team facilitated a kickoff workshop with some 2 dozen people in one room to build the journey which would be validated with field research. Discovery also included stakeholder interviews to learn about the system, the various surgical procedures it was intended for, competitors and more. A subset of the team (including me) went to a surgical conference to interview doctors and see competitive products firsthand. Others went to various hospitals across the nation to speak with doctors and staff in their work environments. Some designers were even fortunate enough to witness brain surgeries. Medtronic also delivered a StealthStation—a half million dollars worth of equipment—to our office for us to use in person. All of this material and hands on insight was plowed into the design work.

Coach & Direct

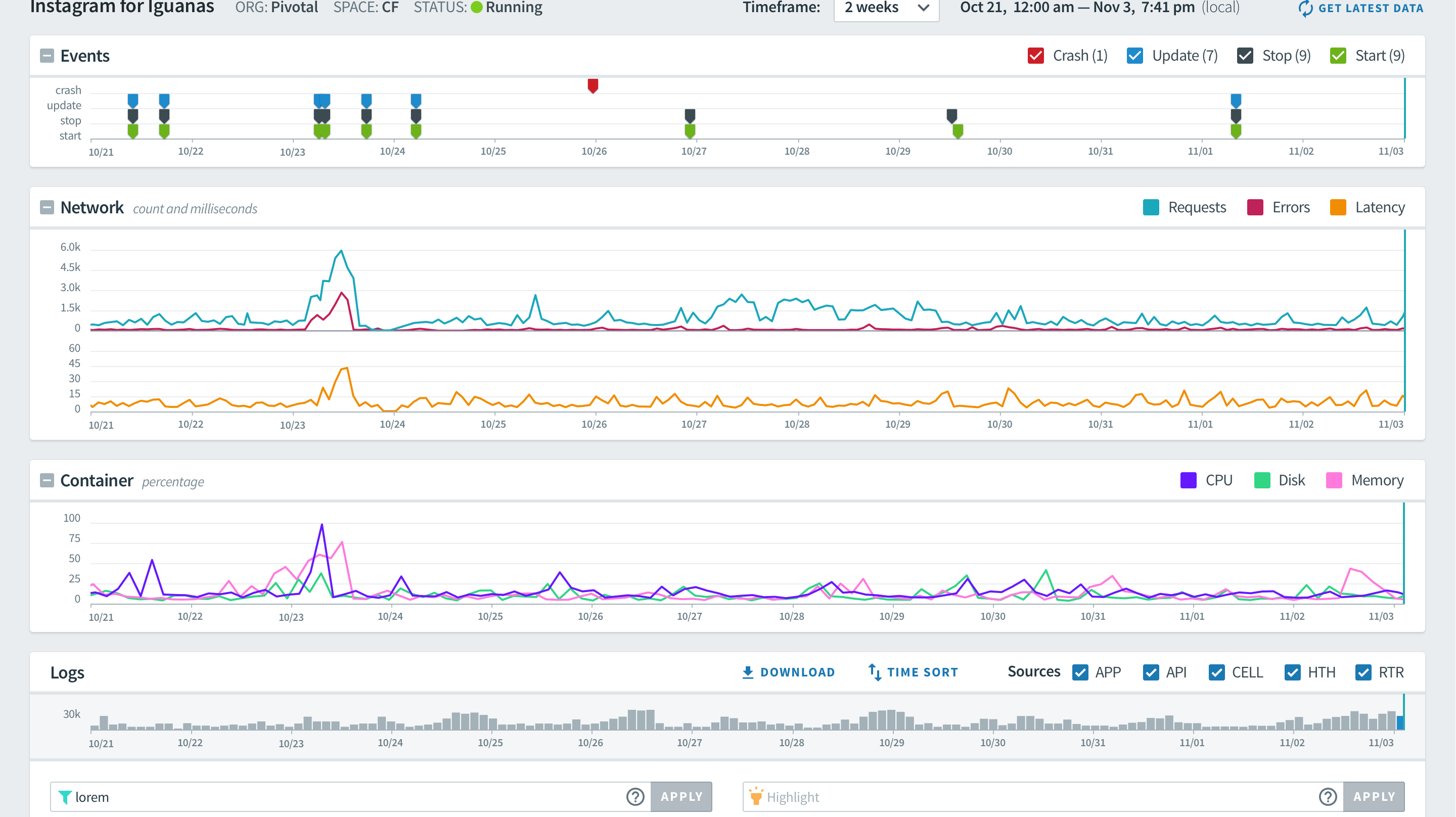

As everyone's knowledge grew, each team took hold of their own tracks of work and took ownership of their workflows. I began to recede in order for the client contacts to direct their attention to each team's lead designer rather than me. Each team, following Slice's version of agile (modfied to the needs of UX), created a regular cadence of design pairing, client pairing, iteration planning meetings, retrospective meetings and testing sessions. I helped keep each team cognizant of upcoming milestones in the engagement when they would all present work to the full Medtronic team for critique.

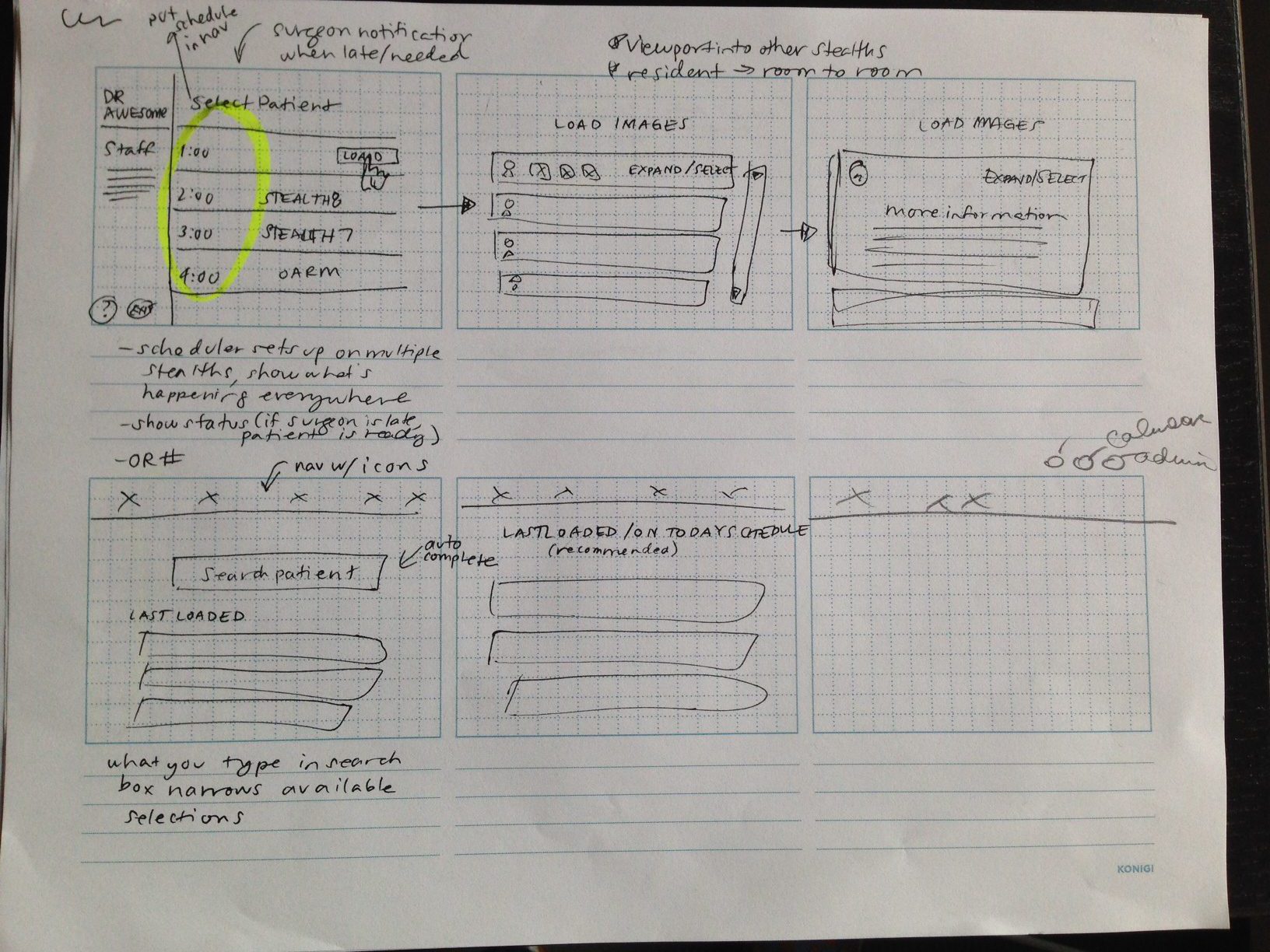

Along the way, I asked questions about their work and rationale while continually referring back to the foundational research and user information. In response—and as teams gained confidence in their solutions—they steadily moved from sticky notes and research oriented output to sketched raw ideas to wireframes with more sophisticated UI and ending with visual design.

During and throughout these phase changes, I teach when and how to include feedback from both internal stakeholders and customer proxies to external users. Slice's success with clients is also contingent on our ability to foster communication across silos and to get the right people into the right room at the right time. Design studios, for example, included not only our designers and the team's points of contact, but also engineers, UXers, marketing and anyone else who could provide a wider set of opinions and input for a more holistic, overall perspective. This allows teams to stay nimble even as they continually refined and focused their work.

My Role

Process and methodology (especially around research) are a large part of what I brought to Slice of Lime and this project tested those areas. With this project, I learned lessons about how to manage large design teams working on a single problem. Coordinating a pair of designers and the client was a typical scenario for me, but the new dynamics at play here were a challenge. Where should I focus my attention? Do I have enough visibility into each team to know they're on track to finish on time? Are teams healthy and well functioning given the competitive nature of three teams solving the same problem? These were the issues I confronted and I was under pressure to learn on the job with enough quickness to avoid inflicting more harm than good. Those on staff also found the assignment challenging, but for different reasons and they doo had to learn on the job. With good communication, we were largely able to avoid tripping over each other while adhering to our contractual obligations.

Lessons Learned

Don't compete with your colleagues

It's unecessary to pit teams against each other to win a challenge. The ethos of teamwork, commaraderie and collaboration will take people further. Exploring different aspects or choosing to focus on different constraints is fine as long as what's learned can be made available to all. We found that team morale differed based on notions that the "better tracks" of work were reserved for better designers. This type of grinding negativity and conspiracy theory blooms when information and transparency are held in secrecy.

Set people & teams up to succeed

As is often the case, the scope of this project was greater than originally projected. Timelines, however, were difficult to adjust as many other Medtronic teams were dependent on our work. While we met deadlines and Medtronic was satisfied to the point of reengaging with us for additional work, there were times when people's work/life balance ran them ragged. I could have advocated for better ways to field people from the start given what I knew about the assignment and each designer's pressures outside of work versus career trajectory.

Be supportive, not heavy handed

As much as it seems contradictory, leaders should limit how much tactical help they offer. If a team struggles to deliver quality work, your tendency is to step in and apply your experience and skill to rectify the situation. However, this approach easily turns into micromanagement and diminishes morale. Instead, broker conversations that help teams help themselves. It's better to leverage a team's sense of autonomy and ownership by facilitating and coaxing them to use their inherent skill, knowledge and creativity to overcome obstacles.